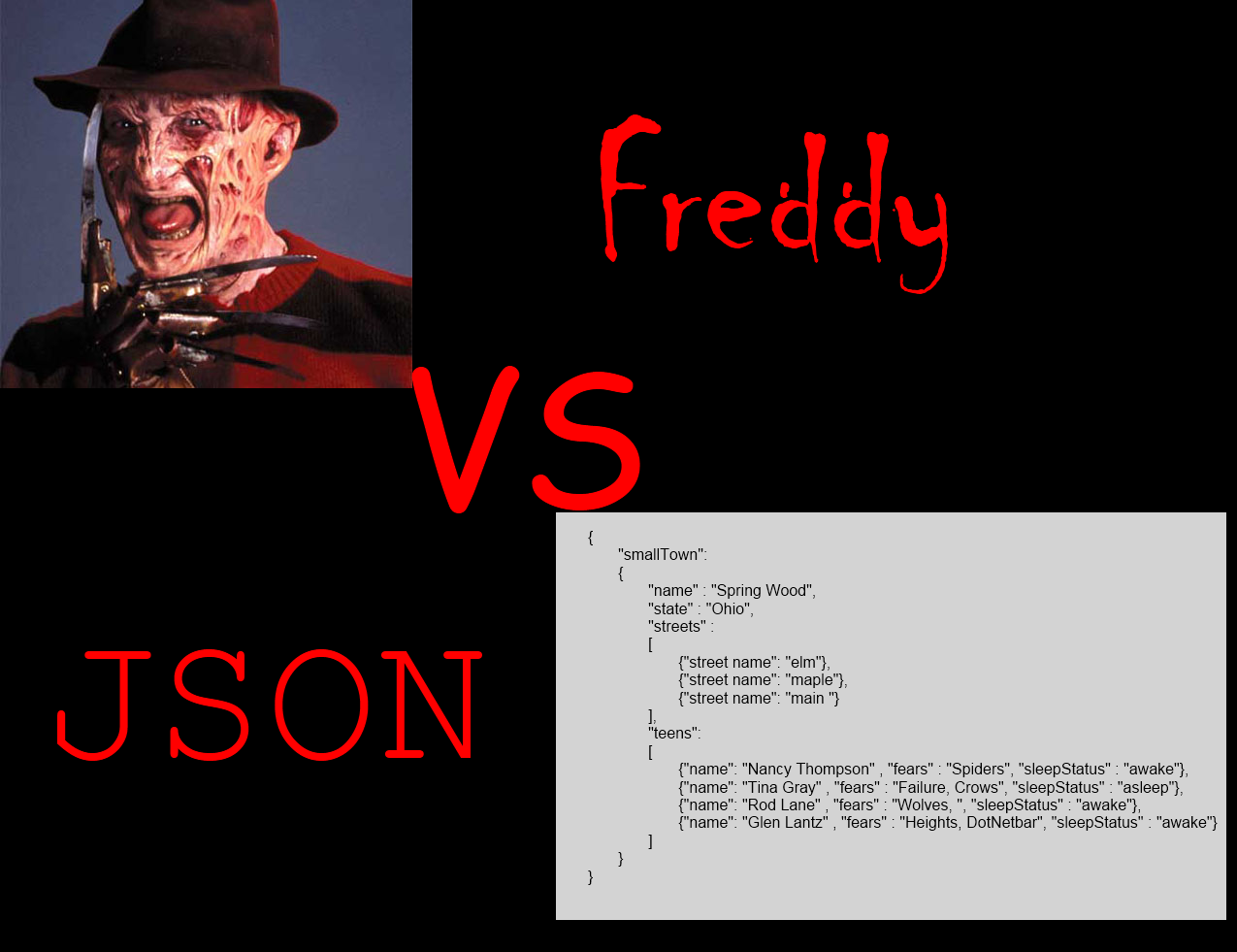

Freddy vs. JSON

Great post by Jeff Atwood, founder of Stack Exchange, on becoming a parent. Well said.

Not for the easily offended, and I don’t agree with all of it, but it’s hilarious when you picture Sam Jackson saying it! ;)

RequireJS - Adventures with an asynchronous script loader

A presentation I created for the dev team at work, published with the blessings of our director of development…

Most of the projects I develop at work are enterprise Microsoft apps, using Visual Studio and Team Foundation Server. Reusing JavaScript in VS projects typically involves either copying the code (violating the DRY principle) or creating pre-build events to copy the code at build time (a little better, but far from ideal)

I’ve been doing a lot of JavaScript application development lately, and really loving James Burkes RequireJS module loader. For a recent project I ended up copying a non-trivial amount of common utilities code, and decided it was time to figure out a better method to centralize common JavaScript code without requiring a script server and related overhead (HTTP requests) and maintenance.

After some experimentation, and discussion with RequireJS author James Burke, I figured out how to develop and build RequireJS apps using a central repository for common JavaScript code. The basic gist is that you specify a HTTP path to the repository code modules during development, (a localhost website) from which the files are dynamically loaded, and a filesystem path (to the source of the localhost website) in the build configuration file. The RequireJS optimizer consolidates the common modules via the filesystem path, along with the local modules, into a single file for deployment.

This allows me to maintain and version control common JavaScript code in a single project, and use that code in separate projects, much the way I do with dll/project references in compiled languages like C#.

main.js with HTTP path(s):

require(

{

paths: {

//various application path aliases

“core”: “//localhost/ipayment.core.javascript/scripts/core”

}

},

[

//direct dependencies

],

function (<dependency>) {

<dependency>.<method>();

}

);

app.build.js with filesystem path(s):

({

appDir: “../”,

baseUrl: “Scripts”,

dir: “../../Build”,

paths: {

//various application path aliases

“core”: “../../../iPayment.Core/iPayment.Core.Javascript/Scripts/Core”

},

optimize: “none”, //”uglify”, “closure” (Java Only), “closure.keepLines” (Java Only), “none”

modules: [

{

name: “main”

}

]

})

Cool!

Tim

I have really been enjoying James Burke’s RequireJS library: http://blog.dohertycomputing.com/post/3466960658/requirejs and have recently applied it to a project at my day job. When it came to testing the application, I decided on QUnit for unit testing, and started poking into using it with RequireJS.

I was able to successfully run tests using the RequireJS approach, i.e., define a test module, with the code to be tested as explicit dependencies, and waiting to start the tests until the module and all its dependencies are loaded. Async behavior is handled via QUnit.stop()/start() as described in the QUnit API: http://docs.jquery.com/QUnit

define(

[

“my/moduletotest1”,

“my/moduletotest2”,

“my/moduletotest3”,

],

function (moduletotest1, moduletotest2, moduletotest3) {

return {

RunTests: function () {

test(“mod1test”, function () {

QUnit.stop();

moduletotest1.ajaxyMethod(arg, function(result) {

deepEqual(result, matchExpression);

QUnit.start();

});

});

test(“mod2test”, function () {

QUnit.stop();

moduletotest2.ajaxyMethod(arg, function(result) {

equal(result, matchExpression);

QUnit.start();

});

});

…

}

};

});

Then in the QUnit page script:

QUnit.config.autostart = false;

require(

[

“UnitTests/TestModule”,

],

function (testModule) {

QUnit.start();

testModule.RunTests();

}

);

Works like a charm!

Nice post by James Burke, author of RequireJS, (which I have fully embraced in my latest production app) on why the Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD) appears to be winning the JavaScript module wars. It’s a clear, concise, and cogent argument.

Node.js is an event-driven I/O framework for the V8 JavaScript engine on Unix-like platforms. It is intended for writing scalable network programs such as web servers. That’s right, a web server written in JavaScript! Server side JavaScript is a very hot topic right now, and the idea of an end-to-end solution with the same language on both the client and the server is a nice idea. While Node is really aimed more at high-performance, high-concurrency asynchronous server development, the “one language” idea is a novel bit of added sugar.

But what’s that, “Unix-like” platforms? What about Windows? Sure, you can run linux on a VM, or on a separate partition, but what if you want to run node directly within Windows?

Well, I came across a post by an Aussie named Tatham Oddie that addressed just that question, and now I have node running on my Windows 7 box!:

http://blog.tatham.oddie.com.au/2011/03/16/node-js-on-windows/

My first node server, displaying “hello world,” is up and running, and I’m juiced to start digging deeper and writing practical server implementations.

My short term goal is to build a simple end-to-end solution with all the pieces I’ve talked about recently: node as the server, RequireJS client-side modules, jQuery Templates, and jQuery DataLink

Stay tuned…

A very good reference outlining the implementation of common design patterns in JavaScript.

Dependency management and modularization are hot topics in JavaScript right now. In classical OO languages like C#, we often take dependency management for granted, as there is an abundance of tools available for this purpose. JavaScript is a powerful, flexible language but still sorely lacking in the tools sector. Traditionally, dependencies have been manually configured by specifying script tags in transitive dependency order. This approach, while effective, becomes tedious and difficult to maintain as the volume of scripts grows. In today’s large-scale JavaScript applications, streamlined and efficient dependency management is becoming more and more crucial.

Related to dependency management is the modular approach to designing JavaScript applications, separating functionalities into physically separate files roughly following OOP’s single responsibility principle: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Single_responsibility_principle. Clearly, this approach lends itself to a large number of files in all but the simplest applications, and dependency management/module load order then becomes critical.

Fortunately, the JavaScript community has taken note, and tools are emerging to bridge these gaps. Among those I researched as candidates were:

YUI Loader from Yahoo: http://developer.yahoo.com/yui/yuiloader/

StealJS, part of JavaScriptMVC: http://www.javascriptmvc.com/docs/stealjs.html#&who=stealjs

Lab.js: http://labjs.com/

RequireJS: http://requirejs.org

As of this writing, I’m leaning towards RequireJS for a couple of significant reasons:

1) It’s a port of the proposed CommonJS specification for modular JavaScript. CommonJS (http://www.commonjs.org/) came out of the server-side JavaScript movement, and defines an API by which functionality can be packaged into interoperable JavaScript modules. CommonJS is gaining real traction, and has a strong change at widespread acceptance.

2) The syntax required to define RequireJS modules imposes minimal impact on how I write modules. It essentially entails just wrapping my modules in the API’s define() function:

//my/shirt.js now has some dependencies, a cart and inventory

//module in the same directory as shirt.js

define([“./cart”, “./inventory”], function(cart, inventory) {

//return an object to define the “my/shirt” module.

return {

color: “blue”,

size: “large”,

addToCart: function() {

inventory.decrement(this);

cart.add(this);

}

}

}

);

So far, I’m really pleased with the implementation. Modules explicitly describe their own dependencies, and the API ensures a file is only loaded once. The API uses asynchronous script loading via insertion of script tags in the document head, allowing browser-legal cross-domain requests. You can specify multiple script paths, and define multiple object contexts so that multiple instances of a module can be defined in a single page.

This is a very powerful, well thought-out API that looks like a good candidate for effective and efficient module loading and dependency management. I’ll post more as I dig deeper…

From jsFiddle.net:

“JsFiddle is a playground for web developers, a tool which may be used in many ways. One can use it as an online editor for snippets build from HTML, CSS and JavaScript. The code can then be shared with others, embedded on a blog, etc. Using this approach, JavaScript developers can very easily isolate bugs.”

Closures are one of the most powerful features of the JavaScript language, and also one of the least understood. Simply put, a closure is an object that retains access to the lexical scope in which it was created. Remember that in JavaScript, functions are first class objects, they can be assigned to variables, passed as arguments etc.

Take the following example:

function myFunction() {

var i = 0;

return function () {

alert(++i);

};

};

var myFunction2 = myFunction(); //myFunction is now out of scope

myFunction2(); //displays 1

myFunction2(); //displays 2

myFunction2(); //displays 3

What happened? The function returned by myFunction retains access to the local variable i - this is a closure. JavaScript maintains not just the returned function, but a reference to the environment in which it was created - including all the local variables in scope at that time.

So, why is this useful? Well, one excellent use is encapsulation, allowing an object to expose a public API whilst keeping it’s internal data and functionality private.

Consider this example:

function myObject() {

var i = 0;

function increment() {

return ++i;

};

function decrement() {

return —i;

};

return {

PlusOne: function () {

alert(increment());

},

MinusOne: function () {

alert(decrement());

}

};

};

var myObjectInstance = myObject();

myObjectInstance.i = 1; //fails, private variable

myObjectInstance.increment(); //fails, private function

myObjectInstance.PlusOne(); //displays 1

myObjectInstance.PlusOne(); //displays 2

myObjectInstance.MinusOne(); //displays 1

Our MyObject function has a locally-scoped variable “i”, and two locally-scoped functions, “increment” and “decrement”. The return value is an object (defined with object literal notation) that defines two functions, “PlusOne” and “MinusOne”. These functions are public, but they access the private functions “increment” and “decrement” via the closure provided by myObject’s context. This is starting to look a little like private methods and variables in classical OO…

Taking it one step further, we can introduce a variation on the classic GoF singleton pattern by making the function execute and return immediately with the following syntax:

var myObject = (function () {

var i = 0;

function increment() {

return ++i;

};

function decrement() {

return —i;

};

return {

PlusOne: function () {

alert(increment());

},

MinusOne: function () {

alert(decrement());

}

};

})();

Our object is now instantiated and ready to use:

myObject.PlusOne();

myObject.PlusOne();

This is generally referred to as the JavaScript Module Pattern, and attributed to Douglas Crockford. For a concise synopsis: http://www.yuiblog.com/blog/2007/06/12/module-pattern/. It’s a very useful pattern, lending itself to modularization of JavaScript code.

There are pitfalls, some of which I’ll go into in future posts. However, carefully used closures lend themselves to clean, powerful, maintainable JavaScript code.

As your JavaScript applications become more complex, it is imperative that you namespace your scripts to avoid naming conflicts and avoid polluting the global namespace. (i.e., the window object)

JavaScript has no built-in support for namespaces, but you can simulate them by assigning your functions as properties of an object.

var NameSpaces = {

Register: function (namespace) {

var nsParts = namespace.split(“.”);

var root = window;

for (var i = 0; i < nsParts.length; i++) {

if (typeof root[nsParts[i]] == “undefined”)

root[nsParts[i]] = new Object();

root = root[nsParts[i]];

}

}

};

NameSpaces.Register(“My.Namespace”);

My.Namespace.myFunction = function() {

…

};

You can now call your new function as My.Namespace.myFunction(), which is uniquely scoped to the window.My.Namespace object, and safely avoid conflict with any other “myFunction” that might appear in another loaded script. Namespacing your functions also keeps the global namespace clean and uncluttered.

Thanks to Michael Shwarz for the Register function in the above closure: http://weblogs.asp.net/mschwarz/archive/2005/08/26/423699.aspx

It is not usually until you’ve built and used a version of the program

that you understand the issues well enough to get the design right.

—Brian Kernighan, Rob Pike, The Practice of Programming

Some photos I’ve taken underwater over the past five years. I don’t have a working camera right now, but I hope to get back to this very expensive and time consuming hobby soon!

I’ve been working with JavaScript quite a bit lately. It’s been part of my skill set for years, but largely for simple DOM manipulation, validation, alerts and the like. With the advent of AJAX, popular libraries that abstract cross-browser constraints, and widespread adoption of JSON as a payload format, JavaScript seems more than ever to be poised for prime time. Add to this the growing number of server-side implementations like Node.js, and JavaScript represents possibly the most important language in web development today.

So, I’ve been digging deeper into client-side application development with JavaScript, and learning a lot in the process of moving from server-side and classical OO development. Libraries such as jQuery, Prototype, and MooTools started to pique my interest a few years ago, and jQuery in particular has become part of my standard toolbox these days. Its clean, closure-based, highly extensible design has made it extremely popular and for good reason.

Recently, jQuery got a huge boost when Microsoft started supporting the library, both by bundling it with Visual Studio and now by contributing directly to the jQuery community with three official jQuery plugins: http://weblogs.asp.net/scottgu/archive/2010/10/04/jquery-templates-data-link-and-globalization-accepted-as-official-jquery-plugins.aspx

Two of these plugins, Templates and DataLink, got me started on a proof of concept at work combining them with ASP.NET MVC 3 to serve JSON payloads to the client application. From there I started digging deeper into JavaScript itself, looking at some more advanced concepts including implementing some of the classic GoF patterns within the context of JavaScript.

In coming posts I’ll share some of what I’ve learned along the way, hoping to shed some light on the ubiquitous but largely underestimated language that is JavaScript.